Movies about imaginary friends have proven to be one of the year’s surprising cinema trends, thanks to John Krasinski’s family blockbuster IF and Blumhouse horror Imaginary – so you’d be forgiven for thinking that this was a universally recognised concept.

However, Yoshiaki Nishimura, co-founder of Studio Ponoc – an anime production house founded by several Studio Ghibli veterans – is quick to tell Zavvi that charming animated adventure The Imaginary was a harder sell in his home country of Japan, where most of the population are unfamiliar with what an imaginary friend actually is.

“If you told this story in a Japanese setting, most people here would see it as something like a ghost story, which completely transforms the core message if that main character becomes a ghost. I thought about relocating the story to Japan, of course, but when only 10 to 20% of the population at the absolute maximum are familiar with this concept, there is the danger of this story getting lost in translation.”

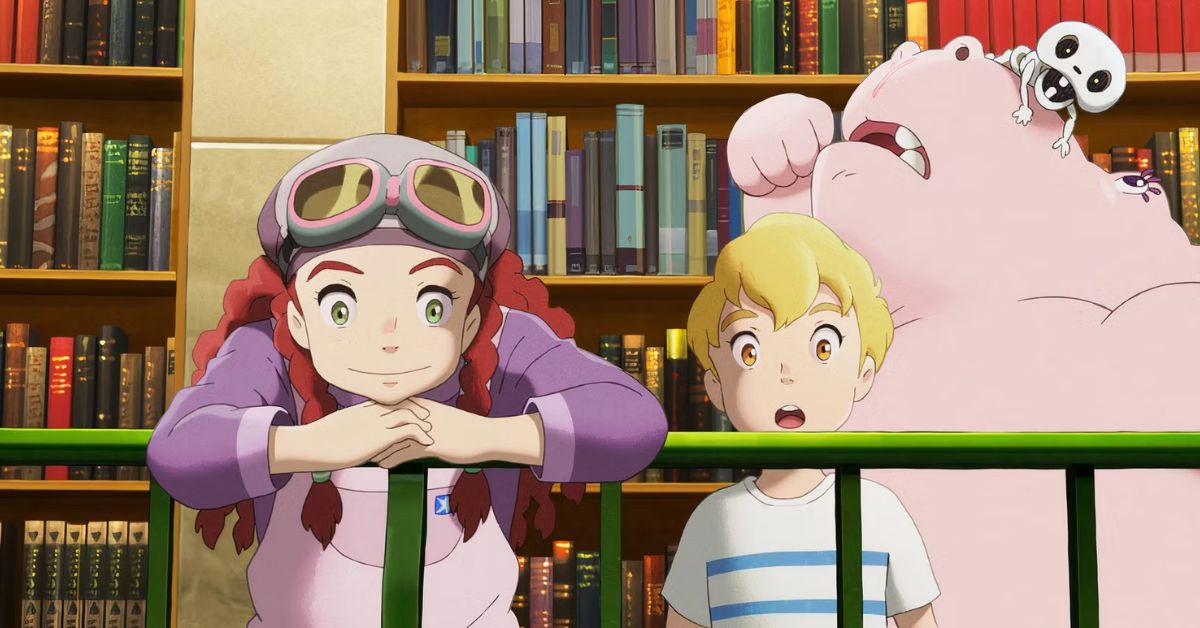

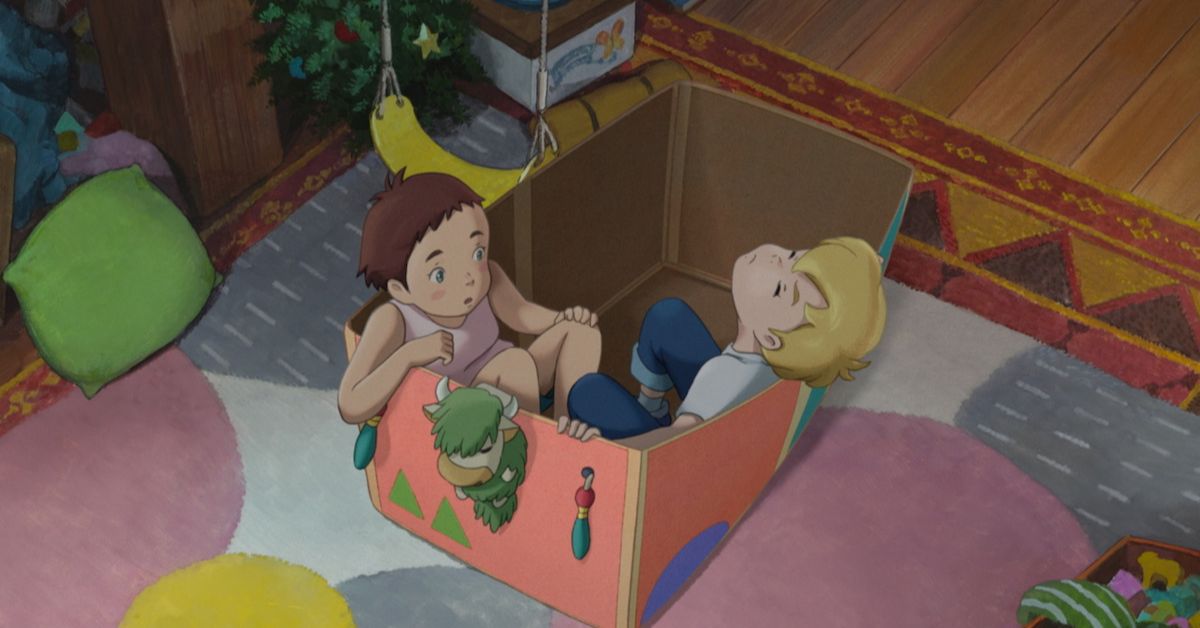

Adapted from a 2014 British children’s novel of the same name by A.F Harrold, the story begins near the end of the friendship between primary school kid Amanda and her imaginary friend Rudger. The pair play together daily, but the sudden arrival of the creepy Mr. Bunting – who consumes imaginary friends whole – signals that she’s about to move on, so he escapes on a voyage to the Town of Imaginaries, where the forgotten friends team up to build new relationships.

Naturally, producer Nishimura didn’t have any imaginary friends growing up – “and if I did, I’ve forgotten them!” – but this subject matter proved close to his heart as both his son and daughter have had imaginary friends, with experiences similar to those of lead human character Amanda.

“The reason why I was attracted to this project and was really curious about the role of imaginary friends is because this story was told from their perspective, not the human character's point of view. I found that very different and refreshing, as it highlighted that they weren’t just one person’s projection, but the living, breathing imagination of another person – a separate entity, which is different but also the same.

“As we started to work on the production, a lot of our memories and experiences came back, which proved as influential as the experiences my children have gone through.”

The decision to keep the story in England was made early on, although the pandemic got in the way of the traditional location scouting process, enabling the team to “cherry pick” their favourite aspects of British towns and cities to create the most idyllic version of the country. The city they took the most inspiration from, however, might come as a surprise.

“You might be able to see some of Southampton in there, especially in the beautiful street corners, and we also aimed to capture a few different elements of London. We couldn’t do the traditional location hunting, so we had a consultant based in England who went around the country taking pictures for us – Amanda’s room is actually based on her daughter’s bedroom, for example.

“I believe the devil is in the details, so in making a movie set in England, we tried hard to capture the specificity of the country. For scenes set in a hospital, we even spoke to a doctor based in the UK, to make sure everything was accurate in some way.”

There’s something quite beautifully uncanny about seeing a picturesque version of England, created through a distinct Japanese hand-drawn animation style, which complements this surreal fairytale. But it isn’t just in the location, but the retelling of the source material’s narrative itself, where producer Nishimura and his team aimed to be as faithful as possible.

He explained: “Reading the original book, I really thought about the essence of each character’s role within this child’s imagination – to understand the fragility of having your destiny be that you will eventually disappear and be forgotten. Breaking down the characters like that is always the first part of our process, before we visualise the story.

“As we’re filmmakers first, not text writers, we have these long discussions about each character’s inner life and back story so we can translate the story in a way that makes the most logical sense visually.”

And perfecting the visuals is part of the reason why The Imaginary arrives nearly two years after its original planned release date, with the producer wanting to pull off an animation trick Studio Ghibli never managed. This involved an extensive collaboration with independent French company Le Films Du Poisson Rouge, whose expertise in both 2D and 3D animation would prove vital for expanding the possibilities of their hand drawn style.

“The technique was simply just adding the texture of light and shadow to our animation, which I’d been pushing for at Ghibli, and we’d been looking for a way to do at Ponoc for a long time. We felt that in order for our films to evolve, a transformation of our animation style would be one of the key factors driving us forward – but we were already in the production stage, so by saying that, I caused a lot of chaos behind the scenes!

“I hold my hand up that I was the one who was adamant about using it, but I think it really enhances the film. It’s a simple way of allowing us to add depth to the emotions the characters are emitting.”

The Imaginary

is releasing on Netflix from Friday, 5th July and in select cinemas from Friday, 28th June.