“At the beginning, I was doubtful whether a book which stirred the kind of emotions it stirred in me could translate into another medium, or if it would lose its impact”, he told Zavvi. “It was only by meeting Marcelo and his sisters to discuss the possibility of adaptation that I decided to go ahead.

“It was a challenge because I’m dealing with a very personal memory, and I knew this family when I was a teenager. I was close friends with many of the characters at the heart of the film, which makes the responsibility of telling their story all the greater.”

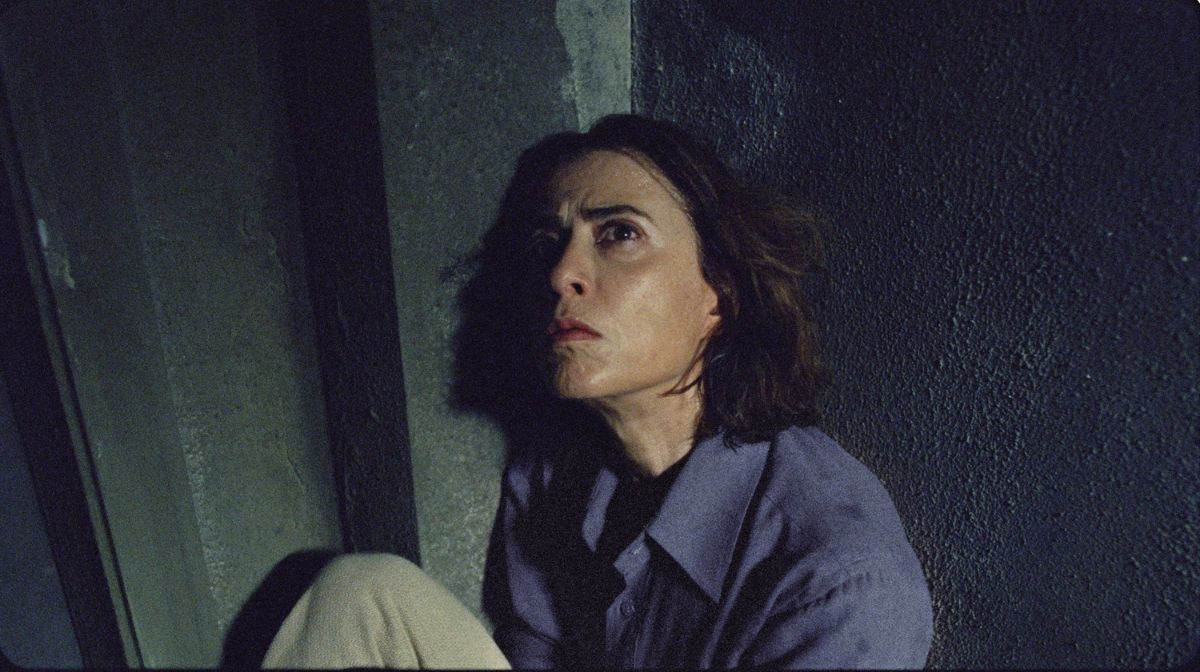

Set in the early 1970s, when Brazil was still under a military dictatorship, the film captures the arrest and disappearance of former congressman Rubens Paiva (Selton Mello) through the eyes of his wife Eunice (the Golden Globe winning and Academy Award-nominated Fernanda Torres). No explanation is given as to why he’s needed for questioning, and Eunice – previously as apolitical as it would be possible to be considering her marriage to a renowned politician – sets out to investigate where the regime has taken him, her husband a Schrödinger's cat she has no way of knowing is alive or murdered.

Salles had previously worked with Torres in his 1995 film Foreign Land, and more notably, worked with her mother Fernanda Montenegro in his 1998 film Central Station, where she became the first Brazilian actress to receive an Oscar nomination. Fernanda senior is credited with a special appearance here, playing Eunice later in her life, when the mysteries of her husband’s disappearance have finally been made a matter of public record.

The director had long been looking for another project to make with Torres, who he credited as being an “extraordinary co-author" in their earlier collaboration.

“It took seven years for the film to come together, and the first years were spent just trying to crack the story, finding a way for this to function as a screen narrative. When it was time to think of actors, it crystalised very clearly that Fernanda was the person who could elevate this material in the way that was needed.

“It’s not by accident that we have two Fernandas playing the same character; that casting was a gift.”

Torres, on the other hand, didn’t assume she would get cast. She was older than Eunice was during the period depicted, and as she’d previously read the memoir, assumed Salles had just given her the screenplay to read as a friend.

“When he invited me for a coffee to offer me the role, it was a massive surprise to me”, she told Zavvi. “One thing Walter has always insisted, which he learned whilst making Foreign Land, is that cinema is a collective work, and that everybody is an author, he’s just the maestro bringing everybody together.

“This made it difficult for me, because the film and this character were already defined by the time I had arrived. We all wanted to make a movie she would recognise herself in, which didn’t nod towards melodrama; she never cried in front of anybody or didn’t see herself as a victim, but she wasn’t tough by any means, she was a gentle person in exceptional circumstances.

“She managed to be intelligent and persuasive as hell beneath that unassuming smile – I mean, she forced the state to recognise an assassination! The difficulty was finding the balance between depicting her as this gentle mother, who is much more feminine than I am, and this figure who was a hell of a fighter, who is so much more than just a parent.

“Walter comes from a documentary background, and he directed us in a way that made us let go of our dramatic instincts. There are many scenes where we don’t look like we’re acting, like we’re just being a family, and those are all credit to Walter.”

Salles describes the film as his “most personal” to date, wanting to do justice to a family who he knew from his formative memories, as well as the turbulent political period he came of age during.

“The glimpses of memories I have of the military dictatorship are in the film, because for me, I remember the joy of that family, and this is a story of a family unit who lived the way they lived as a form of resistance to the state. They were robbed of that joy as our country was robbed of a future and exploring that is what persuaded me to make the film; seeing the personal journey of a family intertwined with the collective journey of Brazil through this time.”

Although Torres can’t directly relate to the family’s trauma during these years, reading the screenplay reactivated many of her own long forgotten memories of growing up during this time. Being from an acting dynasty meant she had her own very specific recollections of how her family dealt with a dictatorship infringing on all corners of public life.

“One of the first words I ever learnt growing up was “censorship”” she laughed. “I was born during the dictatorship, and by the time I was five years old, I already had an understanding of what that meant through my family’s work – they were always afraid of the censors coming to see previews of plays the day before opening, as they had the power to not just cut dialogue, but forbid them from going ahead with immediate notice.

“The film ushered back a lot of other memories of that time; the house feels like my house, and Eunice looks like my mother in the 1970s. Shooting there, it smelt like home, and I got a call from my brother after he saw the movie and he said that was our childhood; he saw us in Marcelo and the little sister.

“I feel like the house is another character in the movie, which I felt even more strongly the day Marcelo came to visit the set, when he told us it smelt like home. Walter would never describe himself as such, but I think he was obsessed with recreating that family home, to the point that just stepping in there felt like time travel; a lot of the preparation was just spending time with the family in that space, so we could get a sense of the light and joy which defines the first part of the movie.

“We shot chronologically, so by the time I was taken to do the prison scenes, I began missing that set – I really had begun feeling like it was my house. When I came back to the set, it just didn’t feel the same, which is reflected in how Eunice views it when she returns from jail.”

Paiva’s memoir became a best-seller in Brazil following the election of the far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who didn’t disguise his admiration for the military dictatorship. Fears of resurgent fascism helped the story resonate – and were also a large factor in why it took the film adaptation so long to get made, with the country’s culture sector becoming anxious that a new wave of government censorship would be on the horizon.

“We went through four years of silence in Brazilian culture”, Salles reflects. “And one of the reasons we wanted to make this film was because we believed we needed to offer more reflections on the past which hadn’t been completely exhausted in cinema.

“We needed to offer a more vivid depiction, which doesn’t just dig in that direction, but speaks to how that history informs our present and warns about our future. It’s only by understanding where we came from that we can ask ourselves where we want to go, and who we want to be as a nation, and posing that question gave greater texture to the film.

“Andrei Tarkovsky had a quote that cinema starts when everyone making a film feels like they’re part of the same artery, looking in the same direction in unison. Understanding what we wanted to say about the present through the past helped us find that artery, to find a way of expressing that message with a sense of restraint which reflected who that character was; she had a volcano of rage brewing inside of her at the state of her country, but she never totally spilled, so we couldn’t underline anything in the same way.”

While it has been an awards success, with a surprise Best Picture nomination making it the first Brazilian film to ever receive the accolade, it shouldn’t be overlooked that the film has resonated with audiences too. It became the highest grossing Brazilian film at the country’s box office post-pandemic, topping the charts for several weeks and even keeping Wicked off the top spot in the musical’s opening weekend.

It was a relief for Torres, who was worried the film would be attacked by the vocal supporters of former President Bolsonaro – its overwhelming success shut them up.

She explained: “We’re releasing this just after a moment when all culture in our country was being attacked as perverted and immoral by the people in charge, and it’s very tough to fight back and create in that climate. I was worried that this film would be received in a binary way, with sympathies aligning along the political spectrum, but it felt like the whole country empathised with this family, could relate to them, could see their fears of living in a country where this could happen reflected onscreen.

“I thought the film would be attacked politically, but instead it taught a new generation about this dictatorship by centering this family’s experiences, understanding how authoritarianism can break a family, see the ones closest to you killed with no explanation. When dictatorship comes, you can die, and it’s not something you can fall in love with – I've seen younger people express interest for an idea of a dictatorship, because a “strong leader” can solve problems, but they never do.

“Democracy is full of problems, but through this story, I hope we’ve reminded audiences that the other option shouldn’t be considered for a second.”

I’m Still Here is released in UK cinemas on 21st February.