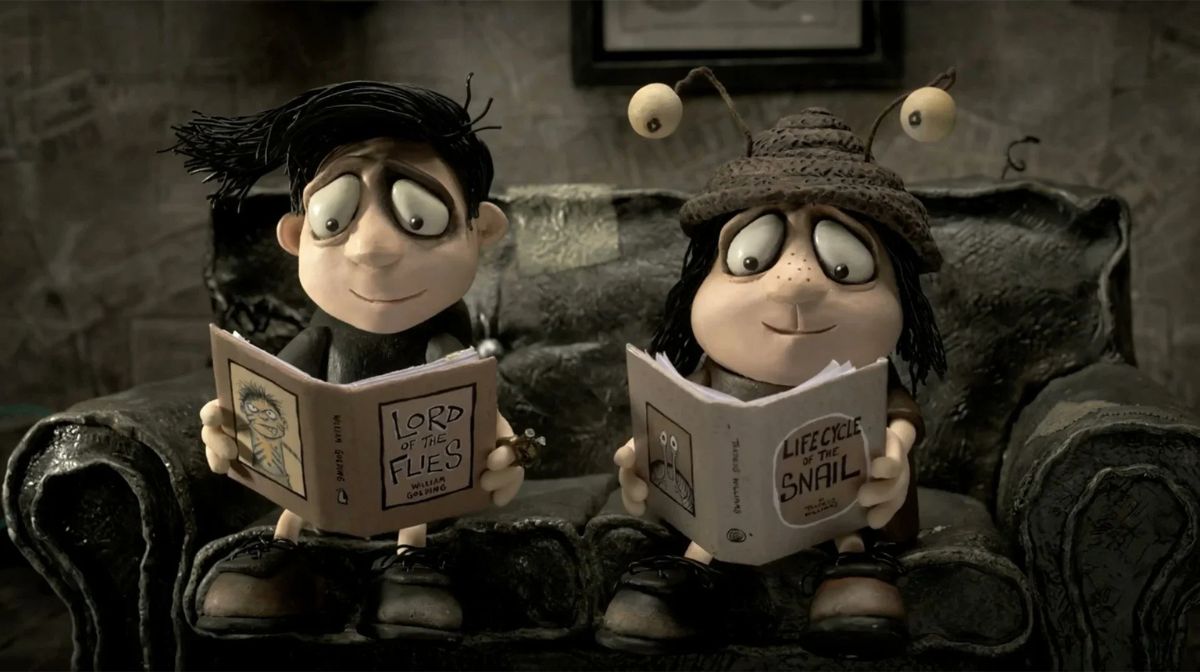

With his Oscar-nominated latest film Memoir Of A Snail, director Adam Elliot - the Australian stop-motion maverick behind Mary And Max – set out to punish viewers.

“I’m always terrified of making something that’s too dark for audiences, and I try to balance out the darker themes with a whole bunch of gags”, he explained to Zavvi. “But with this film, I wanted the audience to really suffer!

“I want them to feel like they’ve been dragged through the mud, and that it has felt unrelenting, but I want to reward them for hanging in there and suffering alongside Grace by the ending. I always say that if you’re not an emotional wreck by the end of one of my films, I’ve failed!”

Elliot’s first feature in 15 years follows Grace Prudel (voiced by Succession’s Sarah Snook), a bullied young girl separated from her twin brother Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee) following the death of their father. Grace remains in Canberra, struggling to fit in without her brother’s protection, whilst her brother is sent to a remote Outback community to live with a religious fundamentalist family, who realise he’s gay at a young age and attempt to “convert” him.

The director’s critics have accused him of making “misery porn”, although he’s keen to point out that the central characters in each of his films have taken inspiration from his family and friends, and he wouldn’t dream of writing anything exploitative which could be traced back to them. Here, the character of Grace is equally inspired by both of his parents, who became hoarders later in life – seeing a documentary about extreme hoarders made him want to explore the condition more.

“When writing, it’s always best to apply the adage that you should never let the truth get in the way of a good story, but Grace is by far the most truthful character here. The hoarding is based on my parents, but she’s also largely taken from a friend of mine who was born with a severe cleft palate and had a lot of operations on her mouth – she was bullied and teased a lot in school, but grew up to be a confident, extroverted adult.

“They’re all very different to Grace in many other aspects, but my process always begins with that kernel of truth from a life experience that either I or someone I’m close to has had.”

Elliot tends to spotlight characters with disabilities, with previous protagonists across his features and shorts diagnosed with conditions including Cerebral Palsy and Asperger’s. It makes him the rare director to explore the lives of disabled characters, which sadly remains a novelty onscreen – especially in the realm of animation – although he doesn’t want his work to be seen as notable in this way.

He explained: “I’m always surprised that I’m the only one who seems to be doing this, it just feels natural to look at the people around me and tell their stories. I don’t look for people with disabilities, it just so happens that I have a higher degree of family and friends with these issues than most.

“I never use the word disability though, as a lot of them don’t see themselves as having one – I'm more interested in how we define ourselves by the imperfections we perceive ourselves to have, which are just flaws we must embrace. I have a friend with Tourette’s who certainly wouldn’t like to have the condition, as it’s been a real difficulty for him, but I’ve met others with that condition who are proud of their ticks, so it really depends, no one depiction of a condition like that is the definitive one, or the “right” one.

“I’m mostly motivated by finding the extraordinary in the ordinary. My characters aren’t heroic, but they are everyday people who can be brave and courageous, and that all begins with them coming to terms with what they perceive as imperfections about themselves.”

As he’s an openly gay filmmaker, I was curious as to whether Gilbert’s experiences of conversion therapy were close to anything he’d personally experienced, and if he functioned as a surrogate for the director himself. Thankfully, this wasn’t the case, at least not on a literal level.

“I’ve had friends who have been forced through gay conversion therapy, which is a torturous, unnecessary and ultimately ridiculous ordeal. It’s like trying to change the colour of somebody’s eyes, and in many countries it’s still not totally banned, including here in Australia.

“Symbolically, Gilbert’s suffering is an extension of the struggles I had growing up but isn’t directly lifted from my own. I just wanted him to go through something traumatic, and I thought of other ways for him to be tortured, but this one just felt right!

“I don’t want my films to be educational about these situations, but I want them to challenge and enlighten viewers and make them consider these subjects more deeply. I want the audience to shed a tear as much as I want them to laugh and be entertained, and the tears I want them to shed the most I hope are tears of happiness by the end.”

Which brings us back to the “misery porn” criticism. His films are generally well-received by critics, audiences and awards voters alike, but as he’s upfront about making films which reduce viewers to emotional wrecks, does he understand why some take against his work in this way?

“I absolutely do”, he continued. “But I believe it’s the writer and director’s job to provoke an emotional response in the audience; the films I love seeing the most are the ones that move me, and cinema is ultimately about making that connection with viewers.

“I don’t think it’s exploitative, as I think I treat my characters with a lot of respect, and I feel that anybody calling my films “pity porn” are missing the point. There’s a lot of sincerity in what I do, and my big aim is to make films which are nourishing, to tell stories that present positive human values that are life affirming and validating to those who need it most.

“Every day I receive emails from around the world from people who relate to my characters and have been through similar struggles, which is incredibly moving. Although, with all this said, I must be honest, I love reading negative reviews – I want to learn from my mistakes, and every now and again, somebody will write something that convinces me they’re spot on about my work!”

Memoir Of A Snail is undisputedly not for kids – in fact, it’s the second R-rated animation to receive a Best Animated Feature nomination, after Charlie Kaufman’s Anomalisa in 2015. This didn’t stop many confused parents taking their kids to see it when it released in Australian cinemas last year, which the director believes shows just how much stigma there is towards the genre, to the extent many still can’t conceive of “adult animation” as a concept.

“My films aren’t for little kids, but I know a lot saw this one, and I worry that they shouldn’t be watching it – but weirdly, I have found that little kids have enjoyed it as the bleak stuff goes over their heads, and they just love that it’s about collecting snails. I have found that this is getting the best response I’ve ever gotten from teenagers and young adults who identify with the character of Grace, but they’re okay to watch my movies, they’re over 12!

“I do keep wondering why this perception that animation is just for children persists, despite all of the examples of successful adult animation over the years. I think it all goes back to the fact everybody is brought up with Disney and Warner Bros movies as kids, but if you look at many of those films from the 1940s to the 1960s, they’re racist, sexist and homophobic – I'd argue they’re less suitable for children than my movies!”

After the long gap in-between films, Elliot is now looking forward to the future and hopes production on his next effort will begin soon (“I’ll almost be 70 if I take another 15 years, so no longer than five!”). By that point, audiences might have finally recovered from the emotional fallout of seeing Memoir Of A Snail.

Memoir Of A Snail is released in UK cinemas on Friday, 14th February.