But what exactly is it that makes a Hitchcockian thriller, well, Hitchcockian? The foundation of a Hitchcockian thriller is the director’s belief in the power of suspense over surprise. When interviewed by Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock defined the difference between the two via two scenarios where there is a bomb underneath a table.

In the first scenario, Hitchcock and Truffaut are talking when suddenly there is an explosion. This comes as a total surprise, with everything before the boom having been plain and ordinary.

In the second, the audience sees the bomb beneath the table. It’s set to detonate at one o’clock, and the clock in the scene shows it is quarter to one. Suddenly, every second becomes vital as the audience agonisingly awaits the bomb’s explosion.

In scenario one, Hitchcock gives the audience a momentary surprise. In the second however, he creates sustained suspense and a greater thrill.

Whilst early Hitchcock thrillers like The Man Who Knew Too Much and Sabotage adhere to Hitchcock’s philosophy, it’s the 1948 masterpiece Rope that best demonstrates it.

Filmed as a single‐take within one room, Rope begins with two students murdering a college friend for kicks. Following the murder, they hastily stash the body in a chest, which they proceed to leave in full view of a dinner party, all of whom are waiting for the victim to arrive.

By beginning with the murder, and then spending the rest of the film with the chest on full display to us and the two killers, Hitchcock ratchets up the suspense by leaving us waiting for somebody to stumble upon the grizzly truth.

The film’s combination of a single location setting and intricate, incriminating camerawork is classic Hitchcock, and famously Hitchcockian thrillers such as David Fincher’s Panic Room owe a great debt to the trail Rope blazed.

Not content with suspense alone in defining his thrillers, another key tenet of the Hitchcockian thriller is the bait‐and‐switch, wherein our expectations are pulled from beneath us by a daring twist midway through the film.

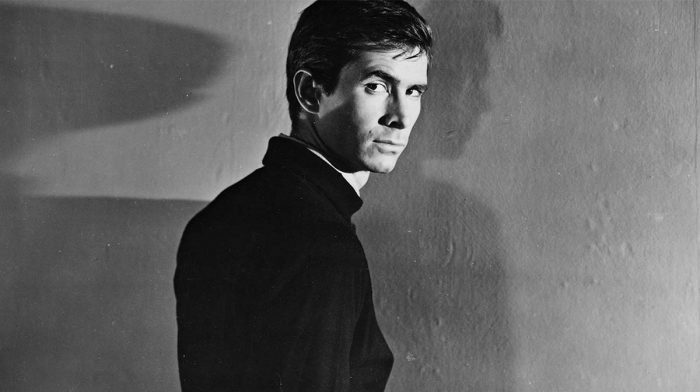

Though works like Dial M For Murder had seen Hitchcock effectively execute the manoeuvre before, the most famous example comes in the 1960 horror‐thriller Psycho.

The film begins with Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane stealing $40,000 from her employer’s client before going on the run. Our initial expectation is of a cat‐and‐mouse thriller as Marion evades the police, and thus the suspense in the film’s first act comes from us knowing Marion stole the money, and waiting for the police to catch on.

However, at the first act’s apex, Marion ‐ and the film itself ‐ leaves the expected path, entering unknown territory.

When Marion steps into the shower at Bates Motel as mild‐mannered creep Norman Bates spies on her through a peephole, her brutal murder changes the course of the film entirely.

From there, our fear for Marion morphs into a fear of Norman and his domineering mother, and where previously we had feared the police catching her, we instead are left in suspense awaiting what Norman and Mrs Bates will do when the police arrive.

In three minutes of film, Hitchcock entirely transforms Psycho in cinema’s most shocking bait-and‐switch.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iE_zfaQjcYg&t=8s

That twist has been the benchmark for many a Hitchcockian thriller since. Most recently, the phenomenal Parasite has reminded us of the power of a perfectly executed bait‐and‐switch, with Bong Joon‐ho’s thriller stunningly changing tack in an eight minute sequence Hitchcock would have loved.

On top of creating suspense and shocking audiences with bait‐and‐switches, maybe the most lingering trademark of the Hitchcockian thriller is its exposure of our own voyeuristic ways.

With his 1954, gaze obsessed masterwork Rear Window, the director irreversibly changed our relationship with film, adding an uncomfortable new dimension to the thriller.

The film stars Jimmy Stewart as Jeff, an injured photographer cooped up in a stuffy New York apartment block, who finds himself spying on a neighbour he suspects of murder.

From his own eyes, to binoculars, to a long‐focus lens, his obsessive watching grows more and more intense alongside our own as viewers.

Iris shots beg our close attention, whilst Hitchcock’s manipulation of our expectations through limited sight-lines and a confined setting make us acutely aware that we are caught in a Russian doll of gazes.

As Jeff stares at his neighbours across the way, so too do we, going a step beyond even as we ultimately watch on for our own thrills when Jeff’s spying places him in jeopardy.

Hitchcock was the first to make us uncomfortably aware of our role in others’ suffering on screen, and though Vertigo would see him return to that notion powerfully, it is Rear Window that redefined the mechanics of the thriller to include us.

A Hitchcockian thriller then is a mixture of suspense, shock, and unsettling self‐awareness, a technical marvel made by a brilliant mind. But, whilst there are many Hitchcockian thrillers, it’s safe to say nothing can beat a Hitchcock thriller. Happy Alfred Hitchcock Day!

For all things pop culture and the latest news, follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook

Related Articles