Late last year, comedian Rose Matafeo took to Twitter to ask a burning question: “What is the best film that you never want to see again?” she wondered.

Some respondents said downbeat Titanic reunion Revolutionary Road, starring Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio. Others went for Lars von Trier’s Dancer In The Dark, a musical starring Björk as a woman suffering with a degenerative eye condition who ends up on death row.

But one movie was mentioned more than any other, to an overwhelming degree: Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem For A Dream.

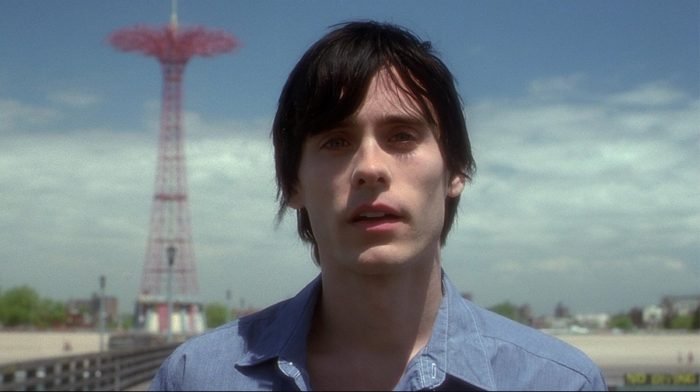

Set primarily in Coney Island, New York, in a non-specific time period that’s somehow simultaneously the ’70s and the ’90s (to make it feel “timeless”, Aronofsky argued), Requiem For A Dream is an unflinching account of four characters’ addictions.

While wiry young scoundrel Harry Goldfarb (Jared Leto), his girlfriend Marion Silver (Jennifer Connelly) and his partner-in-crime Tyrone (Marlon Wayans) get drawn into heroin’s cold embrace, Harry’s elderly mother Sara (Ellen Burstyn) becomes hooked on amphetamine-based diet pills, so desperate is she to fit into an old red dress for a possible upcoming appearance on TV.

Going into dramas of this nature, most viewers might reasonably expect there to be an element of redemption and recovery to these characters’ arcs.

But Requiem For A Dream isn’t your typical Hollywood drama. Based on the novel of the same title by Hubert Selby Jr. (who also wrote Last Exit To Brooklyn), it pulls no punches and hands out no get out of jail free cards.

Aronofsky, who co-wrote the script with Selby Jr., had been inspired to “tell stories” by the author after discovering his work in college, and wasn’t about to start sanding down the edges of his narrative.

Suffice to say, it was a very difficult film to get funded, even though Aronofsky had made such an impressive debut in 1998 with his previous movie, sci-fi thriller Pi. “A lot of people were scared to make it happen,” Aronofsky said.

Requiem For A Dream is, in short, a quadruple-stranded downward spiral. Over three appropriately season-themed acts (Summer, Fall, Winter), it builds in intensity while Aronofsky’s camera uncomfortably creeps ever closer to its suffering protagonists, to a screamingly horrific climax.

In fact, it can be seen as more of a horror movie than a gritty, social-realist drama – except there’s no final-girl escape act come the finale.

Everyone is a victim of Aronofsky’s relentless, invisible monster: addiction itself.

“While breaking [the novel] down I realised that whenever something good was supposed to happen to a character, something bad happened,” Aronofsky wrote the year of the film’s release. “Because of this I couldn’t figure out who the hero was.”

Eventually, he had a screenwriting eureka moment. “The hero was the characters’ enemy: addiction. The book is a manifesto on addiction’s triumph over the human spirit.”

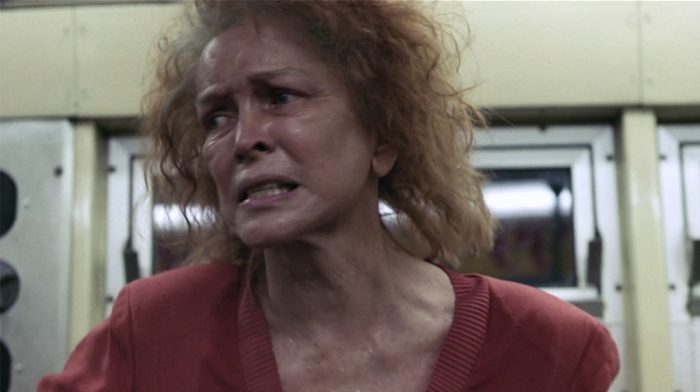

Unsurprisingly, the film was often as tough to make as it is to watch. For Burstyn, especially, who underwent hours in prosthetics to look suitably plump for the early scenes, then later had to endure sequences in which a pill-frazzled Sara is held down and force fed by medical orderlies, and ultimately subjected to electroconvulsive therapy.

Rarely has a lead actress Oscar nomination been more profoundly earned.

Meanwhile Connelly, who before this film was probably still best known for Labyrinth, had to portray Marion suffering some deeply distressing sexual abuse.

“This was hard stuff to shoot,” commentates Aronofsky on the DVD. “For everyone.” But, he adds, it was important to “push those buttons” to show the lengths to which people will go to feed their addictions.

There was some pressure, the director admits, to “have some type of catharsis” in the film. During the opening scene, in which Harry steals his mother’s precious TV to pawn for drug money, Sara assures herself that “it’ll all work out".

But to Aronofsky, the movie wouldn’t have been worth making if he’d tweaked it to render her relatably naïve assertion truthful.

“It doesn’t always work out in the end,” he says. “Anyone who’s lived 20 years on this planet knows that things get f*cked up and they stay that way. I think it would have been undermining Selby’s morality and Selby’s message to in any way soften or lighten this film.”

It’s important to note that, for all its harshness, there is much beauty in Requiem For A Dream. Committing to an intensely subjective visual approach, Aronofsky used a variety of innovative techniques to keep us up close and personal with his characters as their collective grip on reality loosens.

The screen is often split to maintain multiple perspectives and form barriers between characters. At other times, it wobbles with an eerie heat haze, or judders with disorienting fury.

He utilised hyper-montage techniques inspired by hip hop’s cut-and-loop sampling to emphasise the impact of every drug hit, whether from heroin, pills or coffee.

Visual effects were employed in the subtlest of ways (for example slightly shrinking Burstyn’s face in one of the final act scenes) and were deemed so essential to this low-budget production that Aronofsky formed his own mini VFX company to handle them.

There is also the exquisite bitter-sweetness of the score, composed by former Pop Will Eat Itself front-man Clint Mansell in collaboration with the Kronos Quartet.

It’s powerful stuff. So powerful, in fact, that two years later it would be covered by a full orchestra to sell the expansion of Peter Jackson’s Middle-earth in the first trailer for The Lord Of The Rings: The Two Towers.

In truth, Requiem For A Dream is a film which does demand, and deserves, repeated viewings. But, similar to Aronofsky’s most recent visual poem, the divisive mother!, it cuts so close to the bone you can be forgiven for leaving it at just the one.

And, let’s be honest, it strikes hard and true enough to stay with you for your entire lifetime.

For all things pop culture and the latest news, follow us on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and TikTok.