Believe it or not, it’s 20 years since the release of Ridley Scott’s Hannibal, the big budget sequel to 1991’s Silence Of The Lambs and a thriller that was itself a decade in the making.

Controversial at the time of its release, the movie has been remembered less fondly than the Oscar‐winning predecessor, and edged out further by the success of the TV remake, also called Hannibal.

While both that film and show are worthy of praise, we think this second entry in the Anthony Hopkins trilogy deserves a little bit more love for bringing a different side to such a well-known character.

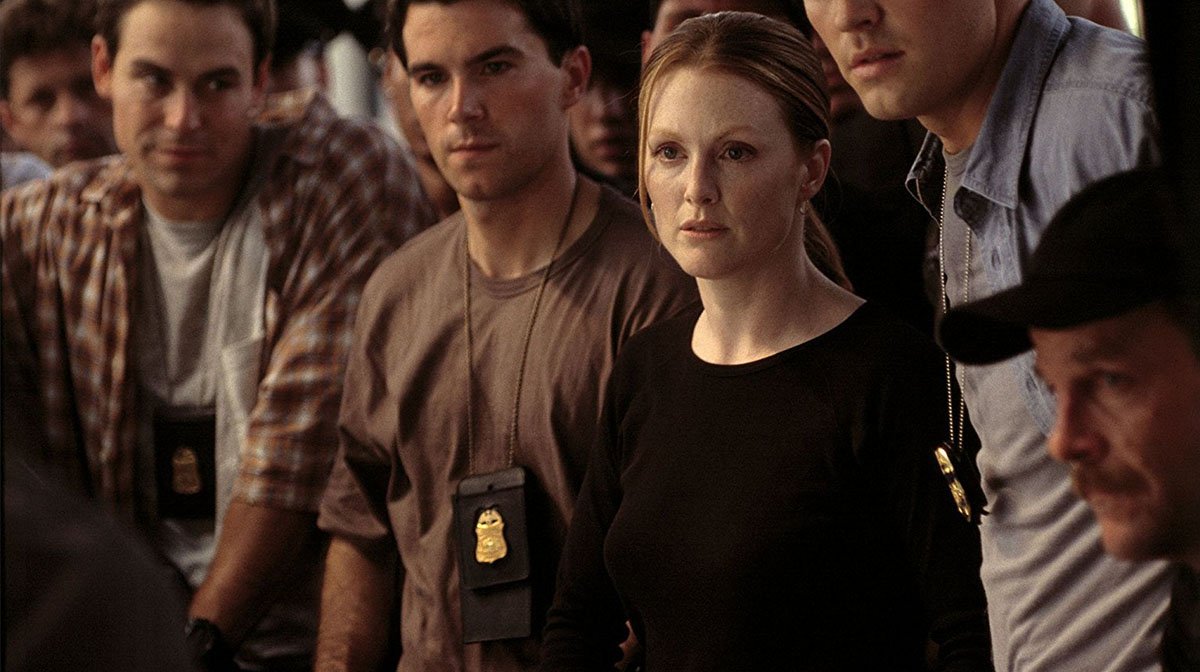

Set a decade on from the first film’s events, we find Clarice Starling (Julianne Moore) firmly established in the FBI. Her misogynist male superiors leap on the chance to bury her career when a raid on a drug lord goes wrong.

While fighting against their judgement, she receives word that Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Hopkins) has resurfaced in Italy, and is back on the FBI’s most wanted list.

Working outside of her jurisdiction, she tries to get to the doctor before a corrupt Italian Police Inspector named Rinaldo Pazzi (Giancarlo Giannini) and Mason Verger (Gary Oldman), a victim of Lecter’s.

However, one by one Hannibal begins to turns his predators into prey.

It’s difficult to convey how big a cultural hit Silence Of The Lambs was in the '90s. A box office hit that swept the Oscars, it became a go‐to movie reference parodied by everyone from French and Saunders to Jim Carrey. Even the US version of The Officesatirised one of Lecter’s killings in 2009.

As such, Hannibal suffered upon its release for the crime of being a very different film. It is grandiose where Silence was gritty. What the previous film did in the shadows, Hannibal does in full view.

There’s a kind of revelry in the violence and gore, from Hopkins’ ritualistic hanging of Pazzi to Verger’s plan to feed Hopkins to some pigs. It’s this graphic nature that meant Silence director Jonathan Demme and the first Clarice Starling, Jodie Foster, declined to be involved.

While originally citing a scheduling conflict, Foster would later reveal she felt the story of Hannibal “trampled” on the character she held dear.

Viewed on its own merits, however, the violence is no worse than a lot of horror movies that would come after. There is also a certain justification for it.

This is the only time in three movies that we would see Hopkins’ Lecter ‘in the wild’, and not behind a glass window. Living as a free man under an alias in Florence, it makes sense that he would indulge his love of killing, always keeping within his own twisted moral code (he is described as only wanting to “eat the rude” as a form of public service).

He revels in this freedom. He’s not the caged animal that Starling first met, he’s now indulging all of his desires in a city filled with beauty and violence. He adds playful little phrases to his correspondences with Clarice, and signs off with an ominous “Ta‐Ta”.

His presence is also followed by a beautiful music cue from Hans Zimmer’s soundtrack, a few haunting notes of piano heard at the end of the piece Dear Clarice.

It’s part of the lavish feel that director Scott brings to the film. Yes, there are certain unusual choices such as an opening credits sequence that shows Hannibal’s face created by a flock of birds, but in general Scott expands the scale into a globe trotting horror/thriller that, like the good doctor himself, indulges in beauty.

Scott also picked an interesting cast. Stepping into Clarice’s shoes was Moore, a '90s sensation following hits Boogie Nights, Magnolia and The Big Lebowski.

As Starling she’s harder than Foster’s portrayal, representing the decade of experience that she has gone through. No longer having to put a forced grin on workplace sexism, she responds strongly and holds her ground when she is accused of having a “smart mouth” or “combative attitude”.

She’s a woman who has fought in every step of her career, and Moore capably builds on the legacy left to her.

Just as with Silence, the real villains in Hannibal are all around Lecter and Starling.

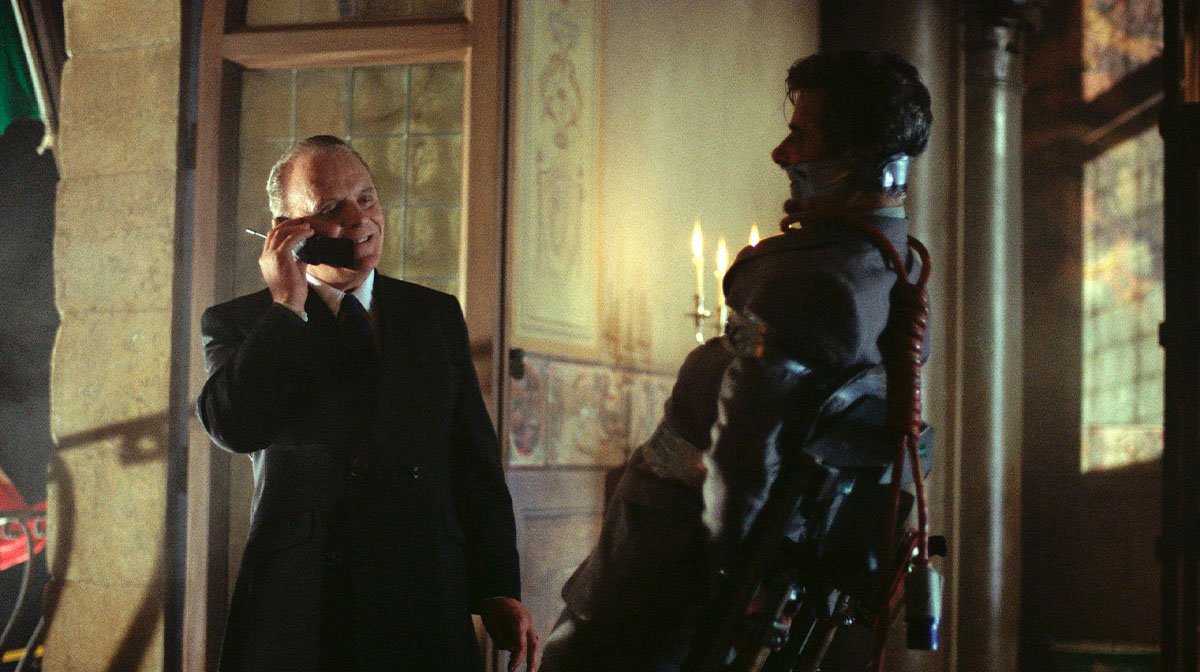

Pazzi is a corrupt cop out for reward money, and breaking rules to cover his tracks. Then there’s Oldman as Verger. Unrecognisable under a mountain of prosthetics, he’s a truly twisted antagonist.

It’s revealed that Verger was a child abuser, leading to Lecter drugging him and making him peel his own face off. Like Hannibal, Mason attempts to push Clarice, and has his own flourishes of dialogue (“seemed like a good idea at the time” he quips when recalling his mutilation).

It’s over‐the‐top, but never anything less than captivating.

The final act brings about one of the most controversial points in the film, a scene where a drugged Clarice is made to witness Hannibal cook the brain of still‐living Justice Department Official Paul Krendler (Ray Liotta), then feeding it to him.

A scene brought over from Thomas Harris’ original book, it’s still a lot to take in on camera, although still fitting into Lecter’s value system.

Krendler is a crude sexist, out to get Clarice after she spurned his advances. He’s also homophobic, saying he “figured (Lecter) for a queer”. As such, you aren’t crying too much when he munches on his own grey matter.

The more pressing issue happens away from the gore. Scott addresses the question mark hanging over the relationship between Hannibal and Clarice.

Verger asks “does Lecter want to f*ck her? Kill her? Eat her? Or what?” The answer is none of those three.

There is a darkly romantic thread running through the film, but leaning towards affection more than sex or love. Starling is repulsed by Lecter, but also forever changed by her experiences with him.

Lecter is never close to harming Clarice, even the drugging was to save her life after being shot. He reveals something at the end, in the kitchen as Starling tries to prevent him from escaping.

“Would they give you a medal, Clarice, do you think?” he asks. “Would you have it professionally framed and hang it on your wall to look at and remind you of your courage and incorruptibility? All you would need for that, Clarice, is a mirror”.

Therein lies the reason for his affection. Despite his evil appetites, Lecter is a man able to recognise good in people. Having looked into the darker recesses of the minds of everyone he meets, he only sees purity in hers.

It’s not enough to make him turn himself in, but enough to choose to cut his own hand off instead of hers when he tries to escape the handcuffs binding them together.

To say Hannibal is a masterpiece, or even to superior to Silence Of The Lambs, may be stretching things.

It’s a very different film, and not without flaws, but its place in history is undeserved being lumped in with the much blander prequels Red Dragon (2003) and Hannibal Rising (2007).

Taken on its own merits, it’s a big Hollywood thriller that takes one of cinema’s most iconic performances in a different direction, and provides more than a few hauntingly brilliant scenes.

For all things pop culture and the latest news, follow us on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok.